Identifying People Who Are Using Harmful Behaviour

Being able to recognise people who use harmful behaviour

You will come across people who use harmful behaviour in your day-to-day line of work. Recognising the signs and behaviours of people using harmful behaviour can help inform any further action you may need to take. If you are unsure of how to proceed then consult your organisation’s Safeguarding Lead. If anyone is in immediate danger always call 999.

What types of behaviours may be abusive

Understanding the intention behind an individual’s behaviour is a useful way to assess if they may be abusive. When thinking about an individual’s behaviour consider if an average, reasonable person would behave in this way. Below is a list of examples of abusive behaviours, however, this list is not exhaustive.

If they are checking up on their partner/ex-partner/family member frequently – listening to their phone calls, reading their messages, tracking their location, calling/messaging them to find out where they are or who they are with.

If they are frequently putting their partner/ex-partner/family member down – calling them names, criticising them, humiliating them, making false accusations about them.

If they are trying to control their partner/ex-partner/family member – telling them who they can or can’t see, where they can or can’t go, what they can or can’t wear.

If they are trying to limit the contact their partner/ex-partner/family member can have with doctors, social workers, or other professionals – stopping them attending appointments, insisting on attending appointments with them, not allowing them to speak for themselves/speaking for them.

If they try to stop their partner/ex-partner/family member from having financial freedom – stopping them gaining or maintaining a job, not allowing them ownership of their own finances, incurring debt in their name.

If their partner/ex-partner/family member is afraid of what they will say or do – if they are being physically violent, emotionally abusive, intimidating, withholding essential medication or care, forcing them to engage in sex when they do not want to.

People who use harmful behaviour may come to your attention in many different ways

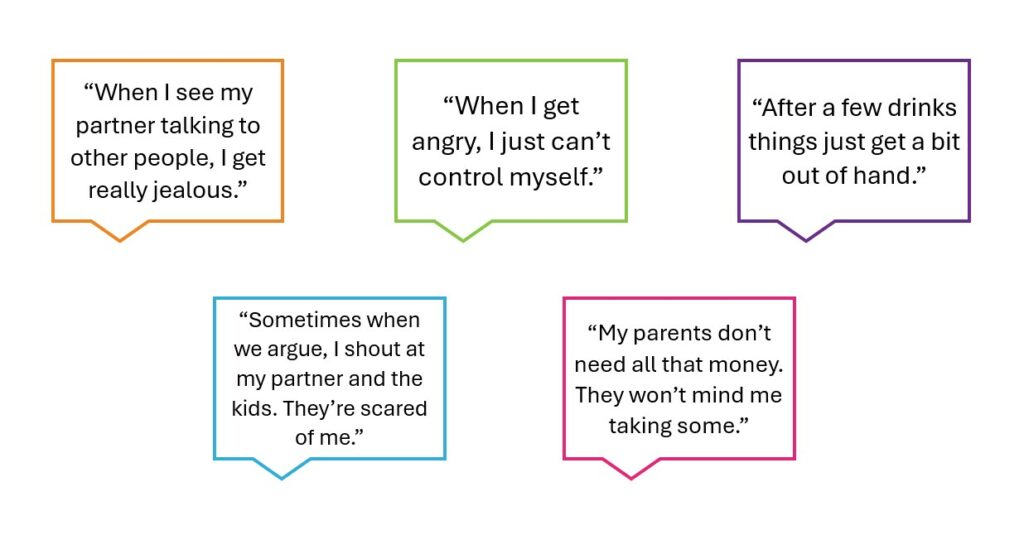

There is no one-size-fits-all when it comes to people who use harmful behaviour, however, below is a list of common examples. This list is not exhaustive:

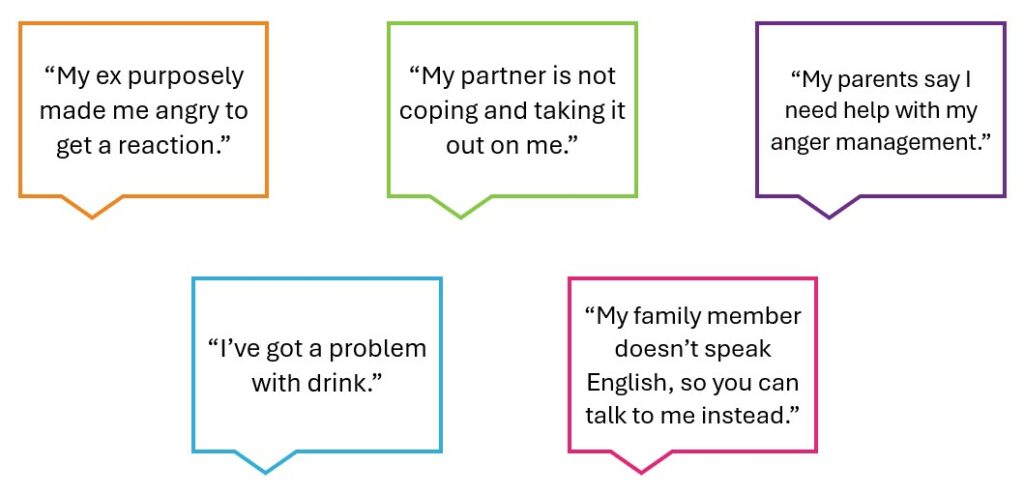

They may not take responsibility for their abusive behaviour and may excuse or justify their actions to gain sympathy, or portray themselves in a better way, e.g. “my ex purposely made me angry to get a reaction.”

They may present themselves as the victim and their partner as the abuser. Some people who use harmful behaviour do this as a way to maintain control of the victim, whereas others do this because they genuinely believe themselves to be victims, e.g. “my partner is not coping and taking it out on me.”

They may be seeking help for their harmful behaviour following a serious incident; the police may have been called, their partner/ex-partner/family member may have been badly hurt, or their partner/family member may have warned they will leave if the individual does not seek help, e.g. “my parents say I need help with my anger management.”

They may seek help for other problems connected to, or exacerbating the abuse, such as alcohol or substance misuse, mental health problems, gambling addiction, etc, and may not give any indication to the abuse, e.g. “I’ve got a problem with drink.”

They may be persistent in attending their partner’s/family member’s appointments and even give the impression of being caring. They may speak on behalf of their partner/family member, even when they have the ability to voice their own opinion. Some people who use harmful behaviour may translate for their partner/family member who cannot speak English, this may be to ensure they cannot disclose the abuse, e.g. “my family member doesn’t speak English, so you can talk to me instead.”

Perpetrator Typologies

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) refers to physical, sexual, psychological, or economic abuse by a current or former partner. Johnson (1995) outlines four distinct forms of IPV; Intimate Terrorism, Violent Resistance, Situational Couple Violence, and Mutual Violent Control. Each form has different dynamics, patterns of behaviour and motivations for the abuse.

Intimate Terrorism (IT)

Intimate Terrorism is a pattern of coercive control where one partner seeks to dominate and control the other. They will intentionally use emotional, physical, psychological abuse, or a combination of these. Power and control are the motivation behind the abuse which is often severe and frequent in occurrence. Males predominantly perpetrate this form of abuse against females.

An example of Intimate Terrorism: one partner isolates the other from their friends and family, monitoring their daily movements, accessing their phone to check who they have been speaking to, and using threats or physical violence to maintain control of their partner.

Violent Resistance (VR)

Violent Resistance is when a victim uses violence against a perpetrator in response to the abuse they have endured. Violent Resistance is reactive and an act of defence which is not motivated by control, but through a need to escape or stop the violence. This typology is often seen in victims of Intimate Terrorism. Commonly females will use Violent Resistance when defending themselves against male perpetrators. A couple can be mistakenly labelled “as bad as each other” however, it is more likely there is a power imbalance and both Intimate Terrorism and Violent Resistance are occurring.

An example of Violent Resistance: a victim of abuse defends themselves by using physical violence against the perpetrator.

Situational Couple Violence (SCV)

Situational Couple Violence differs from Intimate Terrorism as it arises from specific conflict situations where one – often both – partners engage in violence, however, there is not a power imbalance between them as neither individual is using violence as a way to control the other. This typology is rarer than the others, the violence is usually less severe and perpetrated by both parties with no ongoing cycle of fear.

An example of Situational Couple Violence: a couple gets into a heated argument, and one partner reacts impulsively with physical violence towards the other.

Mutual Violent Control (MVC)

Mutual Violent Control on face value may seem similar to Situational Couple Violence, however, the motivation, dynamics and severity of abuse greatly differs. Both partners may use violence to gain or maintain control over each other. Control is the primary motive for both parties and there is a pattern of ongoing power struggle and violence by both individuals. This typology is less common than the others, but highly destructive.

An example of Mutual Violent Control: A couple argues frequently about issues such as money, jealousy, and parenting; during these arguments both individuals are physically violent to each other. Both partners try to control each other by going through the other’s phone, telling them where they can and can’t go, and demanding to know where the other person is at all times.

It is important for domestic abuse specialists to establish which typology an individual falls into, as this helps better understand and address the abuse. The cause, impact, and intervention needed can differ for each typology. In your role you will not be expected to determine which typology an individual falls into, but it is helpful to understand the different typologies.

Further Support – Respect Phoneline

Respect Phoneline have designed a guideline for frontline workers who may interact with people who cause harm in their daily work.

Principles

There are two important principles which should inform your work:

- Safety first. Your primary aim of work with perpetrators should always be to increase the safety and wellbeing of victim-survivors and their children. You should recognise the need for behaviour change, but your priority should always be to help reduce harm.

- Do no harm. Take all reasonable steps to make sure the support you offer does not exacerbate or generate additional risks for victim-survivors and their children.

The 6 key steps to guide your work

Engage perpetrators taking 6 key steps:

- Look/listen

- Ask

- Assess risk

- Respond

- Refer

- Record

More information on the six steps can be found within the Respect – Guidelines for working with perpetrators of domestic abuse. For further advice or support, practitioners can contact Respect.

Telephone: 0808 8024040

Email: info@respectphoneline.org.uk

Web chat: www.respectphoneline.org.uk

If you need help to change your behaviour please contact Compass the Domestic Abuse helpline and referral service for across Essex.

Whether you’re seeking help for yourself or someone else, COMPASS can guide you to the right support. Call 0330 333 7 444 or visit essexcompass.org.uk